Best Diamond Cuts Explained!

Choosing the best diamond cut is a crucial decision when selecting an engagement or wedding ring. The cut not only influences the diamond’s brilliance and sparkle but also adds unique character and meaning to the jewelry piece. In this article, we’ll explore different diamond cuts, delve into the best choices for engagement rings, and discover the symbolism behind popular engagement ring cuts.

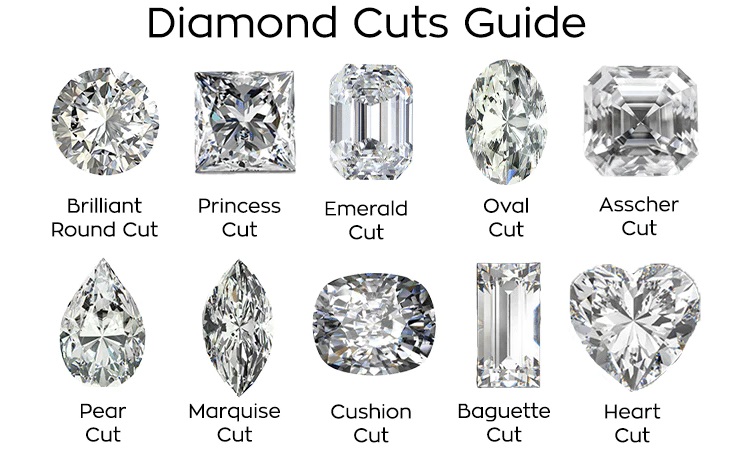

What Are Different Diamond Cuts

Diamonds come in various cuts, each with its own distinct characteristics. Here are some of the most common diamond cuts:

Round Cut: The round cut diamond is the most popular and classic choice of the diamond shapes. It is characterized by its circular shape and features 57 or 58 facets, including the culet. The round cut maximizes brilliance and sparkle, making it a timeless and elegant option.

Princess Cut: Princess cut diamonds are square or rectangular with pointed corners. This cut combines modern aesthetics with brilliant sparkle, making it a popular choice for those seeking a contemporary look.

Emerald Cut: Emerald cut diamonds are rectangular with cut corners. They have a step-cut faceting style that emphasizes clarity and elegance over sparkle. This cut is known for its clean lines and sophistication.

Asscher Cut: Similar to the emerald cut, the asscher cut is square with cut corners. It also features step-cut facets but is typically smaller and more brilliant. Asscher cuts offer a vintage and Art Deco-inspired appearance.

Cushion Cut: Cushion cut diamonds have square or rectangular shapes with rounded corners, resembling a pillow or cushion. They are known for their romantic and antique-inspired look, combining brilliance with a softened outline.

Oval Cut: Oval cut diamonds are elongated and feature the brilliance of round cuts. They are known for their flattering appearance and versatility, making them an excellent choice for those seeking a unique yet classic option.

Pear Cut: Pear cut diamonds, also known as teardrop diamonds, have one pointed end and one rounded end. They symbolize elegance and are often chosen for their distinct and sentimental shape.

Marquise Cut: Marquise cut diamonds are long and pointed at both ends, resembling an elongated oval with tapered ends. They are known for their dramatic appearance and can create the illusion of longer, slender fingers.

Radiant Cut: Radiant cut diamonds combine the elegance of an emerald cut with the brilliance of a round cut. They feature square or rectangular shapes with cropped corners and are known for their vibrant sparkle.

Heart Cut: Heart-shaped diamonds are a symbol of love and romance. They feature a distinctive heart shape with a cleft at the top and rounded lobes. This cut is chosen for its sentimental value.

What’s the Best Diamond Cut for an Engagement Ring

The best diamond cut for an engagement ring often comes down to personal preferences. However, the round cut is the most popular choice due to its unmatched brilliance and timeless appeal. Round-cut diamonds are renowned for their exceptional sparkle and versatility, making them an ideal choice for engagement rings for several compelling reasons:

Proven Quality: Round Cut diamonds often undergo strict grading processes, ensuring that they meet the highest standards of quality. The Gemological Institute of America (GIA) and other reputable grading organizations meticulously assess round diamonds for cut, color, clarity, and carat weight.

Ease of Maintenance: Round Cut diamonds are easy to care for and maintain. Their symmetrical shape and lack of sharp corners reduce the risk of chipping or damage during daily wear.

Excellent Return on Investment: Round Cut diamonds tend to hold their value well over time. Their enduring appeal and widespread demand make them a sound investment, both in terms of sentiment and potential resale value.

10 Engagement Ring Cuts and Their Unique Meaning

Engagement ring cuts come in various shapes, each with its own unique meaning and symbolism. When choosing an engagement ring, it’s essential to consider the meaning behind the diamond cut, as it can add depth and significance to the ring. Here are ten engagement ring cuts and their unique meanings:

Round Cut: The classic and timeless Round Cut symbolizes eternal love and endless commitment. Its circular shape represents the unbroken bond between two people.

Princess Cut: The modern and bold Princess Cut reflects contemporary romance and a strong, confident partnership. Its sharp corners symbolize the strength and uniqueness of your love.

Emerald Cut: Known for its clean lines and step-cut facets, the Emerald Cut represents clarity and poise. It signifies a relationship built on transparency and elegance.

Asscher Cut: Similar to the Emerald Cut but with a square shape, the Asscher Cut offers a vintage charm and Art Deco flair. It symbolizes a love that transcends time.

Cushion Cut: The romantic and antique-inspired Cushion Cut signifies enduring love and comfort in each other’s company. Its rounded corners evoke a sense of softness and warmth.

Oval Cut: The elegant and elongated Oval Cut represents individuality and uniqueness. It symbolizes a love that stands out and shines brightly.

Pear Cut: The distinctive and teardrop-shaped Pear Cut symbolizes a couple coming together to form a perfect union. It represents the emotional connection and shared journey of two individuals.

Marquise Cut: With its dramatic and elongated shape, the Marquise Cut symbolizes regal love and a partnership that stands out from the crowd. Its pointed ends suggest a union that leads to new beginnings.

Radiant Cut: The Radiant Cut combines the elegance of an Emerald Cut with the brilliance of a Round Cut. It signifies a vibrant and dazzling love story filled with energy and enthusiasm.

Heart Cut: The romantic and sentimental Heart Cut is a symbol of passionate love and deep emotional connection. It reflects the love you hold in your heart for each other.

Conclusion

The best diamond cut for an engagement or wedding ring ultimately depends on your personal style, symbolism, and preferences. Each diamond cut carries its own unique charm and meaning, allowing you to select the perfect diamond that resonates with your love story. Whether you choose a classic round cut or a unique heart cut, your choice will symbolize your enduring commitment and love.…